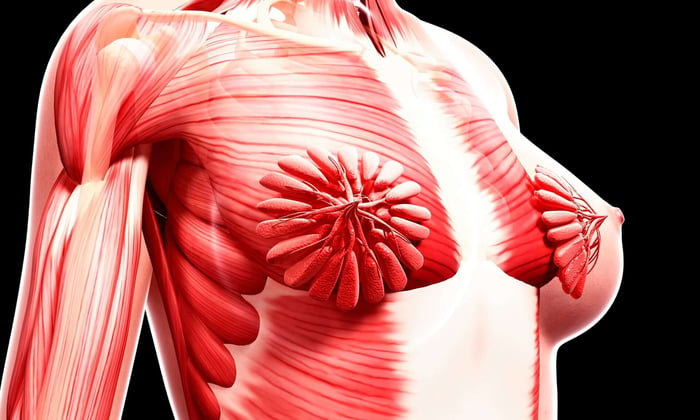

In April of 2019, a tweet (since-deleted) went viral – a photograph of the musculature of a human torso, from the waist up.

When you think of what that picture might look like, there are a plethora of cultural counterpoints to take your cues from. The drawings of Leonarda da Vinci, perhaps; an array of Renaissance statues that stand sentry in front of stately homes and castles throughout Europe; illustrations from How Your Body Works, a collectible bi-weekly magazine, each issue of which came with a different body part, all the better to create your own miniature human body with.

What was different about this image, however, was that it was of a female body – an anatomical illustration rarely seen in, well, anything. The milk ducts, in bloom directly in front of the pectoral muscles, seemed strange and alien: this was not the “default” human body we have come to expect.

It was a shock that was felt once more in an episode of Netflix's The Goop Lab, which focused on the vulva and the female orgasm. The show – which has come under fire for, among other things, its promotion of faith healing, “therapeutic” MDMA dosing and cold-water therapy – chose to show viewers a montage of vulvae, full-frontal visuals so rarely represented on screen.

But when exactly did people with vulvae find their sexual organs being erased from the anatomy books – and are things getting better? Here's a timeline.

500BC: Acmaeon of Croton, ancient Greek philosopher and medical theorist, conducts the first recorded medical dissection of a human body

150BC: Claudius Galen, a prominent physician in Ancient Greece, acknowledges the clitoris, saying, “in women the parts are within, whereas in men they are outside.” He also, tellingly, refers to it as the female body's “failed” attempt at a penis, so there's that.

[large gap in timeline] For several centuries, corpse dissection is rejected by social authorities for a variety of moral and religious reasons.

1486: A treatise on the persecution of witches, called Malleus Maleficarum, or The Witches' Hammer, identifies the clitoris as “the devil's teat”. In its aroused state, it is said to be associated with dealings with the devil, or witchcraft.

1452-1519: Leonardo da Vinci is responsible for a massive swathe of advances in human anatomy, dissecting human cadavers to examine and illustrate them in great detail. Due to an apparent lack of available female corpses – da Vinci's cadavers were often selected from dead criminals – several of his drawings of the female reproductive system got details wrong, more closely resembling animals than humans.

1543: On the Fabric of the Human Body is published by the School of Medicine in Padua. The set of seven books, by Andreas Vesalius, is considered a major advance in the history of anatomy over the work of Claudius Galen, by then several centuries old and long held as the standard in anatomical knowledge.

1545: One of the earliest known dissections of the clitoris is done by Charles Estienne – which would be a promising advance, were it not for the fact that Estienne thought it had a urinary function, and referred to it as the woman's “shameful member”.

1559: Anatomist Realdo Colombo claims to have discovered the clitoris, which he calls “the love or sweetness of Venus” and identifies it as “the seat of women's delight”, casting doubt on the long-held belief that women took no pleasure in sexual intercourse.

17th century: Throughout this time, anatomical theaters are a common sight, with members of the public gathering to watch autopsies being conducted.

1671: English midwife Jane Sharp, in her book, Midwifery Mastered, dubs the clitoris “the female penis” and says that it “makes women lustful and take delight in copulation.”

1672: Just a year later, Dutch physician and anatomist Regnier de Graaf crafts the most comprehensive report on the clitoral anatomy ever published. He writes: “We are extremely surprised that some anatomists make no more mention of this part than if it did not exist at all in the universe of nature... In every cadaver we have so far dissected we have found it quite perceptible to sight and touch.” He also discovered the Graafian follicles, by which we now remember him, although he mistakenly identified them as “eggs”.

18th century: There was a trend throughout the 18th century for anatomical art, whole-body specimens preserved and exhibited publicly.

1774: London obstetrician William Hunter publishes a definitive work on the reproductive system, Anatomia Uteri Umani Gravidi (The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus Exhibited in Figures), for the first time describing the musculature of the uterus.

19th century: Anatomy is determined to be a science, with the result that public autopsies become a thing of the past – dissections are now done in private, in laboratory and medical surroundings.

1844: German anatomist George Ludwig Kobelt conducts a study of the clitoris, drawing the first detailed anatomy of both the internal and external clitoris.

1904: Sigmund Freud, among other things, asserts that the clitorial orgasm is “immature”, while the vaginal orgasm, which women should begin to have once they have reached puberty, is “mature”. Though this has since been debunked, Freud's theories on sex are thought to have been responsible for the culture of sex and sexuality that pervades in the western world today.

1924: Psychoanalyst Princess Marie Bonaparte (okay, also Napoleon's great grand-niece) conducts a study that measures the distance between the clitoris and vagina of 243 different women, concluding that those whose clitorises are further from their vaginas have a more difficult time orgasming during vaginal penetration, while those whose clitorises are closer have a much easier time.

1948: The 25th edition of Gray's Anatomy is released, a seminal work on human anatomy first published in 1858 by Henry Gray, with one notable omission: then-editor Dr. Charles Mayo Goss entirely erases any and all mention of the clitoris from the text.

1953: Alfred Kinsey publishes Sexual Behavior in the Human Female, a companion book to his 1948 publication, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. He asserts that “the clitoris is the center of female pleasure.”

1966: William Masters and Virgina Johnson (yes, as depicted in Showtime's Masters of Sex, by Michael Sheen and Lizzy Caplan, respectively) conduct research in their laboratory, where they scandalously observe sex acts in the flesh. They conclude that the vaginal orgasm is, in fact, comparable to the clitoral orgasm in terms of sexual response, debunking Freud's ideas about “maturity”.

1998: Australian urologist Helen O'Connell conducts the first full autopsy of the female clitoris, mapping out both the internal and external clitoris, demonstrating that the clitoris has two to three times more nerve endings than the penis.

2009: Surgeon Pierre Foldes does the first 3D ultrasound of the clitoris, later conducting the first successful female genital mutilation reversal surgery to remove scar tissue from the vulva and expose some of the internal clitoris in order to return sensation.

2014: Italian research team Puppo+Puppo publish a study in The Journal of Clinical Anatomy asserting, controversially, that both the vaginal orgasm and the G-spot are, in fact, myths.

In 2020, we know more than ever before about female sexuality, anatomy, and the reproductive system – but for all the years that science was focusing on male bodies, there are undoubtedly things that have been missed. Only with an equal focus on both sexes will the scales be balanced, so it will be up to scientists, medical professionals and writers working in the field to bring us up to speed. For your own research, why not start with our list of must-read books?

Further reading:

The Clitoris' Vanishing Act https://projects.huffingtonpost.com/cliteracy/history

The Case for Renaming Women's Body Parts https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20180531-how-womens-body-parts-have-been-named-after-men

Photograph: Shubhangi Ganeshrao Kene/Getty Images/Science Photo Library RF